The Role of Mindfulness During Yoga in Predicting Self-Objectification and Reasons for Exercise

| First of all, thank you to everyone who volunteered to participate in this research which has been submitted for publication. We would also like to extend a special thanks to the yoga instructors at the University of Idaho for allowing us to examine their craft and expertise. |  |

Overview

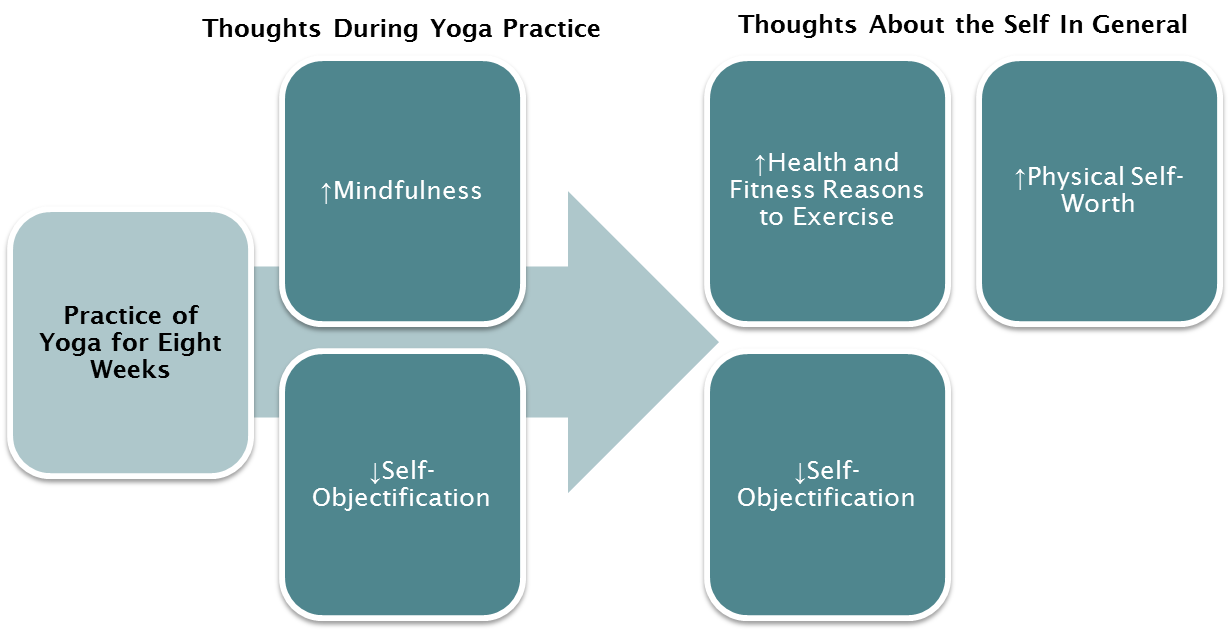

This post is a summary of one of our research projects. The research was conducted at the University of Idaho (UI) by faculty and students of Washington State University. Our intention was to explore how mindfulness during the practice of yoga could be related to changes in body image outcomes and reasons for exercise. We had individuals complete a series of surveys as part of their 8-week yoga course. The surveys included questions about each participant’s body image, physical activity behavior, and reasons for exercise at the beginning of her class. We then asked similar questions at the conclusion of the eight weeks. In addition, yoga participants were also given a survey immediately following some of the classes to gauge how mindful they were during their practice and how much they were thinking about their appearance. Results showed beneficial changes over time in body image variables, health and fitness reasons for exercise, and mindfulness. We also found that mindfulness during yoga was linked to the improvement in body image and internal reasons for exercise over time.

Background

Self-objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) can help to explain body dissatisfaction, body-shame, excessive body surveillance and disordered eating. These patterns have been shown to be a problem for both women and men (Calogero, 2009; Daniel, Bridges, & Martens, 2014; Martins, Tiggemann, & Kirkbride, 2007; Parent & Moradi, 2011; Strelan & Hargreaves, 2005). Exercise can be used to decrease self-objectification (Greenleaf, 2005) and improve the body image variables which are associated with it: body shame, social physique anxiety, and physical self-worth (Lox, Martin Ginis, & Petruzello, 2010). The type of yoga which is most prominently used for exercise usually includes a combination of strengthening physical postures and movement, breathing exercises, and meditation (Riley, 2004). Other researchers who have looked into yoga have recently focused on its positive influence on disordered eating behaviors and body image (Neumark-Sztainer, 2014; Godsey, 2013). Gard and colleagues (2012) found evidence for the role of mindfulness in explaining some of the positive effects of yoga in young adults. This study explores how mindfulness during the practice of yoga could be related to the changes in body image outcomes and reasons for exercise that a participant may self-report.

Who participated in the project?

Of the 202 University of Idaho (UI) volunteers who filled out the first surveys, 148 provided complete enough information over the course of the semester to run statistical analysis.

A small percentage of the participants were male. Eighty percent marked female and 1% stated “other.”

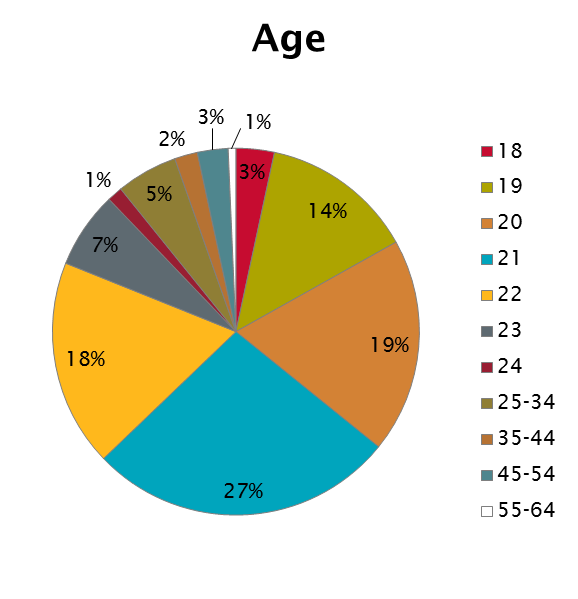

The ages of the participants ranged from 18 to 58, but more than half were under the age of 22 years old. As depicted in the chart above, the yoga classes were mostly young students but the young students were practicing yoga with a somewhat diverse age group.

A very high percentage of the students participating in this study were Caucasian (91%). While the benefits of yoga have not been found to be limited by race, it should be understood that our subject population only included 3% Hispanic/Latino, 1% Asian/Pacific Islander, 1% American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 4% Bi/Multiracial.

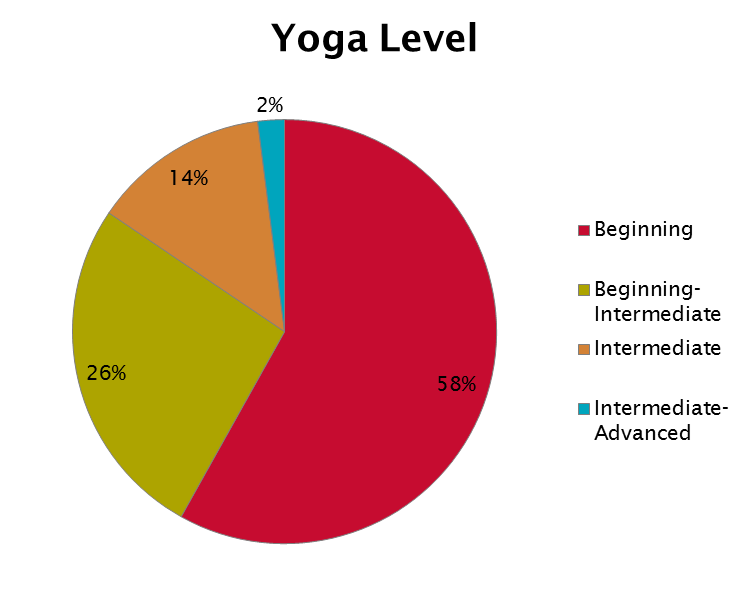

The last demographic to consider is self-described level of expertise in yoga. More than half of the participants described themselves as “beginning level.”

There was a fifth option for “advanced” but none of the participants identified as such.

What was measured?

Surveys measured several different body image outcomes, as well as reasons for exercise and mindfulness during exercise as self-reported by the participants.

Self-objectification and Body Shame

Self-objectification refers to the process by which a person accepts as truth the sexual objectification of his or herself. It occurs when the individual looks at his or herself as an object and engages in chronic self-surveillance. Several questions from the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (McKinley & Hyde, 1996) were used to measure the amount that participants were concerned with how their bodies appeared to others in general and during the yoga practice. Body shame is when a person has a feeling that he or she is being negatively evaluated because he or she has failed to meet the standards of what culturally expected as concerns his or her body. Body shame was also measured using selected questions from the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (McKinley & Hyde, 1996).

Physical Self-worth

Physical self-worth is when a person has a general feeling of happiness, pride, satisfaction, respect, or confidence in his or her body and physical abilities. Six items from the Physical Self-Description Questionnaire were used to measure each participant’s general feelings about her physical self (Marsh et al. 1994).

Reasons for Exercise

The Reasons for Exercise Inventory (Silberstein, Striegel-Moore, Timko, & Rodin, 1988) was used to help understand the different reasons behind each individual’s engagement in physical activity. Three broad categories were used to describe why people exercise: health/fitness reasons, mood/enjoyment reasons, and appearance reasons.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness is the level of awareness and attention paid to the present moment and includes elements of non-judgment, curiosity, acceptance and openness. Directly following a yoga session, we asked the participants questions pertaining to how mindful he or she was about his or her surroundings or body while practicing yoga. We measured the level of mindfulness of each participant directly following yoga using our newly developed State Mindfulness Scale for Physical Activity (Cox, Ullrich-French & French). It is a revision of the State Mindfulness Scale (Tanay & Bernstein, 2013) to specifically measure the parts of mindfulness which will arise when physically active.

What did we find?

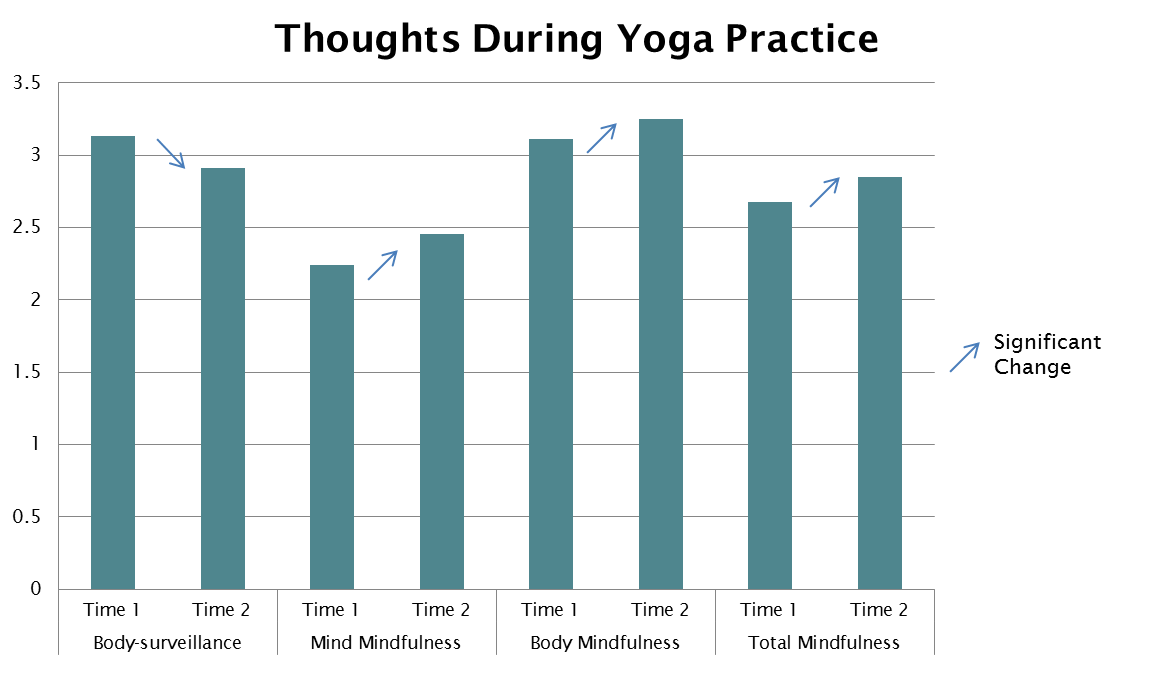

Over the course of eight weeks, the participants on average showed an increase in mindfulness and a decrease in body surveillance during the practice of yoga.

The average level of self-objectification that yoga participants admitted to engaging in during a yoga session was lower at the end of the semester than the beginning. The participants of the yoga class thought less about how their body appeared after a semester of yoga.

When it was measured late in the semester, the yoga participants showed an improvement in mindfulness during a yoga session compared to the earlier measurement. The yoga participants paid more attention to themselves and things around them than they did previously.

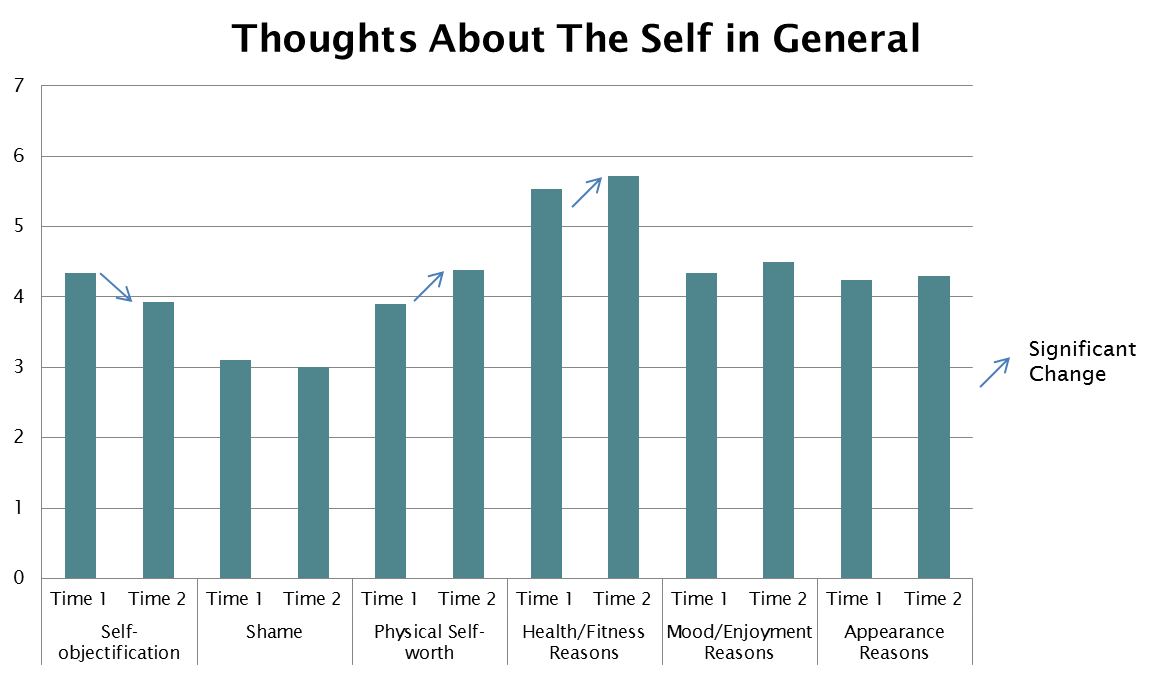

Practice of yoga for eight weeks also led to a healthy change in character traits: self-objectification decreased over time, while physical self-worth and health/fitness reasons for exercise increased.

There were beneficial changes in all of the general character traits over time for the students enrolled in the yoga classes. The only general characteristic changes which were statistically significant, though, were the self-objectification, physical self-worth, and health/fitness reasons to exercise.

The average level of self-objectification that the participants reported in their questionnaires was significantly lower for the yoga students at the end of the semester than compared to the beginning. The yoga students were less prone to engage in chronic self-surveillance at the end of the semester and thought less of themselves as an object.

Participants had a higher value for their bodies and physical abilities after a semester of yoga. The average level of physical self-worth increased significantly at the end of the semester when compared to the beginning of the semester.

It is thought that a person will have a higher rate of exercise adherence if she engages in that activity for intrinsically rewarding reasons. We cannot speak to whether or not the increase in health and fitness reasons for our participants was an intrinsic choice or because of an external pressure to do so. We can say though, that the average number of individuals who engage in exercise for health or fitness based reasons was significantly higher at the end of a semester of yoga.

It was surprising that appearance based reasons to exercise did not drop, but it may be a testament to the strength and persistence of a society which is heavily focused on outward appearance to overshadow the possibly beneficial changes in reasons for exercising in the Inland Northwest.

We also were able to show that the level of mindfulness during a yoga practice contributed to those healthy changes in self-objectification, health/fitness reasons for exercise, and mood/enjoyment reasons for exercise.

Why is this information useful?

This information is exciting and useful for everyone who has considered exercising based off of their body image. Our results could help consumers of physical activity programs be more educated in their choices for types and styles of exercise that they choose to partake in. Perhaps gyms or public health entities should encourage or advertise certain classes more to get men and women to become interested in trying yoga for the first time or being more mindful because of the possibility of contributing to higher levels of physical self-worth and lower levels of self-objectification among their constituents. Physical education teachers who want to encourage healthy ways of thinking about the self should consider adding mindful qualities to their lesson plan. We must emphasize that our results do not show the causality of changes; we were only able to show that the self-reported level of mindfulness that participants of yoga encounter plays a contributing role in the beneficial changes to psychological health.

For more information

Please check back to our lab site for more exciting research and updates on our progress. If you are interested in any of the topics or scales that were used in this study, please visit the references or our resources page. Please feel free to post your comments. Do your experiences with mind/body classes seem to coincide with our findings?